Cyrus Adler Sitting, c. 1890, Smithsonian Institution Archives

by Peter Manseau

Religion has a long history at the Smithsonian, and it was set to music almost from the beginning.

Late in the nineteenth century, the Smithsonian's librarian, Dr. Cyrus Adler, was named the first director of the Religion Division of the Smithsonian's United States National Museum. He made a point of collecting objects that not only showed the global reach of spiritual traditions, but also highlighted the fact that religion is not merely something to be seen, or believed, but heard.

Adler was the son of an Arkansas cotton farmer who in a quintessentially American story ended up becoming an expert in Semitic languages, and a professor of Hebrew at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he famously discovered copies of the New Testament with missing blocks of text that Thomas Jefferson himself had pieced together to create the book commonly known as the Jefferson Bible, which thanks to Adler became perhaps the most iconic religious object in the Smithsonian’s collection. Nor was this Adler’s only brush with the intersection of the presidency and religion: later in life, he served as an advisor to Franklin Delano Roosevelt on matters of concern to the Jewish people.

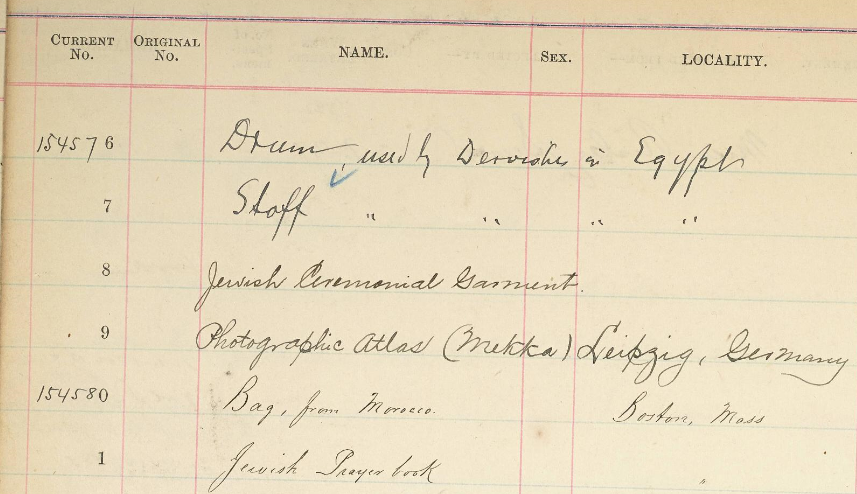

His efforts as a collector, however, extended to all faiths. Hand-written collecting notes from the 1890s include objects from around the world and across the spectrum of belief. On the single typical page shown here, Adler and his fellow collectors recorded a number of Jewish ritual items, a photo album of a pilgrimage to Mecca, a ceremonial bag from Morocco (curiously collected in Boston), and a drum and staff used by Sufi Muslims.

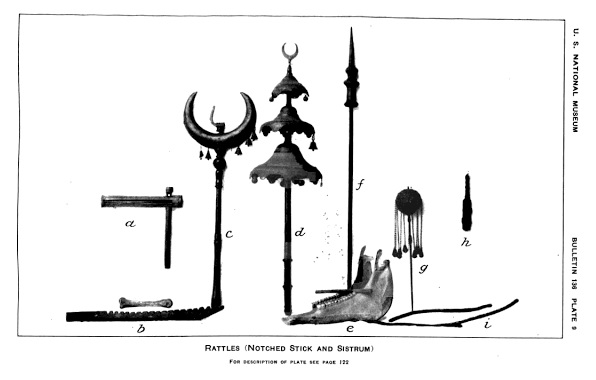

This last item particularly speaks to broader interest that gave a surprising direction to his curatorial work. The Religion Division soon held dozens of religious noise makers from a variety of cultures, including (according to Smithsonian Institution Annual Reports and the regular Bulletins of the National Museum) “a Chinese priest’s gong of bamboo,” a percussion instrument known as a “Turkish crescent,” a bell-covered jingling spear rattle from Sri Lanka, a revolving rattle from the Philippines, and a Dervish rattle from Cairo.

Why all the interest in rattles? In many cultures, the noises such rudimentary instruments made were not as significant as the moments at which they were used. As the Annual Report from 1917 suggests, “the rattle was generally regarded as a sacred object, not to be brought forth on ordinary occasions, but confined to rituals, religious feasts, shamanistic performances, etc.”

Some of these objects no doubt were brought to Washington as examples of strange practices and exotic beliefs that might capture the public’s attention when put on display in the nation’s capital. A Tibetan “exorcising flute” collected in 1888, for example, is described as “made of human femur” and tied with a “lash of human skin.”

Cyrus Adler made no record of the kind of sacred music this macabre device might have made. Yet even in such disturbing cases, something enduring and poignant might have be heard: the universal compulsion to use music to explore and inspire religious experiences.

As part of its new Religion in America initiative, the National Museum of American History is now building on Adler’s work by exploring the spiritual roots of the musical traditions that have shaped the country. Through a series of concerts called Sounds of Faith -- which so far has included colonial English hymns, Wampanoag sacred singing, and the influence of Christianity and Islam on jazz – the Smithsonian will continue to amplify the diverse voices and beliefs that make up the American chorus.

Peter Manseau is the Lilly Endowment Curator of American Religious History at the National Museum of American History