by Regan Shrumm

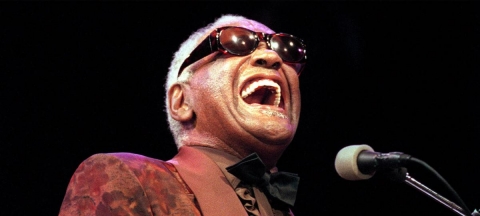

Ray Charles broke down many barriers both as a musician and an African American. He defied genre categorization and frequently intertwined R&B, pop, gospel, and country music in various combinations. Charles also lent his voice to the civil rights movement: he provided financial support to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and even refused to play for segregated concerts in 1961, after receiving a letter from Paine College’s student president. However, not much has been written on Charles’ advocacy for people with disabilities. Perhaps that’s in part because he disregarded his own disability; he stalwartly refused to let it limit him.

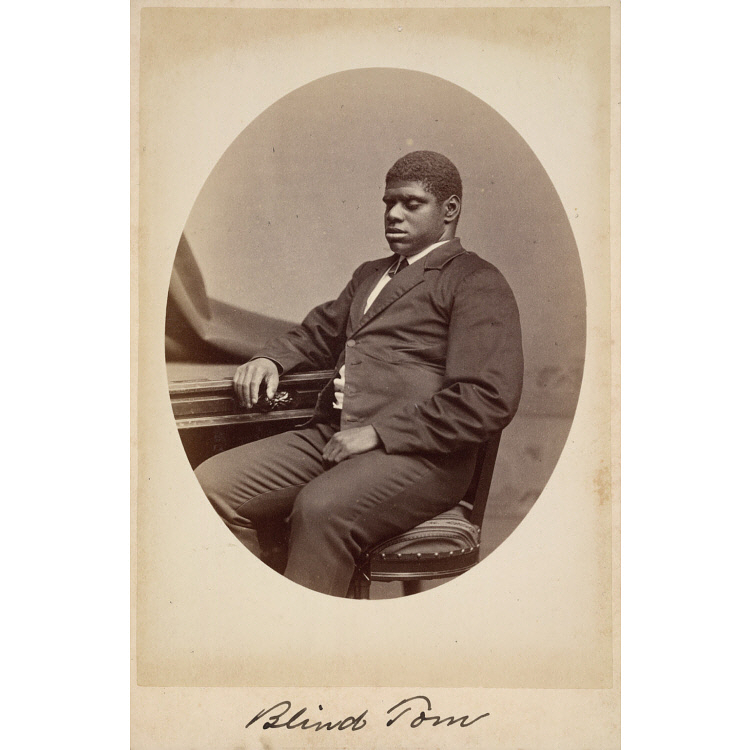

Throughout the mid-19th century and continuing well into the 20th century, medical treatment and information were not equally available to Americans. The number of blind and visually impaired Americans greatly varied across race and economic class. In general, blindness was closely linked with poverty. As many African Americans were living in insufficient conditions, there were a significant number of blind African Americans during this period. Before Charles was even born, many blind African American musicians established national reputations, including pianists Blind Tom Wiggins and singer-guitarist Blind Lemon Jefferson. However, the word “blind” functioned as a professional nickname used to market and exploit their disability. Adding the word “blind” to these musicians’ names served to make them stereotyped “others.” One form of a “blindness myth,” Joseph Witek observed, “is that of the suffering blues singer begging with a tin cup. This formulation casts blindness as the mark of a cruel fate which caps the singer’s degradation and alienates him from his community.”

Born into slavery, Wiggins performed throughout the United States.

National Portrait Gallery, NPG.2000.14.

However, Charles was born in a time when blind and visual impairment was becoming less common in the United States. To maintain Jim Crow laws and practices, southern African Americans were not offered consistent health care, but white physicians began to prognose African Americans, as they knew it could be useful for the general population.

Charles himself was not born blind, but slowly started losing his vision at the age of four, due to what was later diagnosed as glaucoma. While neighbors in Charles’s hometown of Greenville, Florida pitied the boy, Charles’ mother Retha had no patience for sympathy. Charles later recounts that, “When I got to feeling sorry for myself, she’d get tough and say, ‘You’re blind, you ain’t dumb; you lost your sight, not your mind.’ And she’d make me. . .see I could do almost anything anyone else could do.” This determination and rejection of his blindness stuck with Charles for the rest of his life.

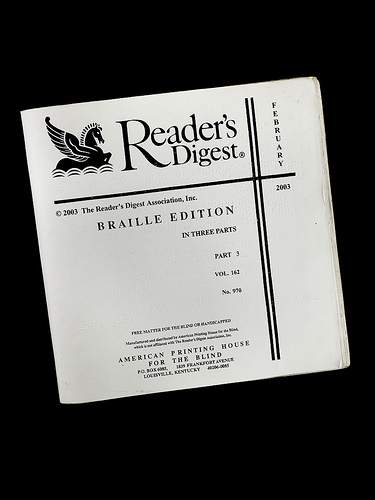

In 1937, the seven-year old Charles was sent to St. Augustine, Florida to attend what was then known as the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind. The school was strictly segregated, dividing males and females as well as African Americans and whites. As the general case was for all segregated schools, the African American facilities were significantly inferior. The African American children were given cast-off supplies from their white sister school, including not only worn furniture, leftover food, and chipped tableware, but also braille books with dots so faded that they were hard to distinguish. While Charles was given an elementary school education, the African American children Were also required to learn practical skills that would help support the school. Charles’ main task was to sew bands around straw booms.

Due to the large braille symbols, this issue is broken up into three parts.

National Museum of American History, 2005.0215.10.

At the school, Charles not only learned braille and sign language as a means of communicating with the deaf children, but also braille music. When Louis Braille first invented the system of raised dots that could be read by fingertip in 1824, he soon later devised braille music. This code still used the braille dots, but had its own entirely separate meaning. However, reading braille music posed difficulties, as Charles had to play the piano with his left-hand while reading with his right, and then switch positions to learn the keys on the other hand. Because of this arduousness, Charles would just memorize a song by heart instead of going back to read the score.

That same year of 1937, Charles became completely blind, as his right eye was removed due to its painfulness. But Charles tried to distance himself from the tradition of blind African American singers before him. Charles refused to play a guitar because, “Seems like every blind blues singer I’d heard about was playing a guitar.” Furthermore, though blind and visually impaired individuals’ use of a white cane had become standard by the 1930s, and in fact was a powerful symbol of independence for many, Charles refused to use the device. Charles affirmed, “Now it’s important that you understand that there were three things I never wanted to own when I was a kid: a dog, a cane, and a guitar. In my brain, they each meant blindness and helplessness.”

Though blind and visual impaired people had been using canes for centuries, the white cane, that was easily visible due to its color, was introduced after World War I.

By the 1930s, white cane ordinances were passed, allowing people carrying the cane to have a right-of-way.

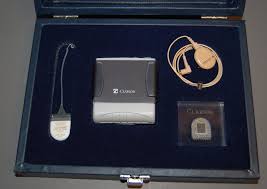

After experiencing chronic ear troubles leading to temporary hearing loss, Charles incorporated the Robinson Foundation for Hearing Disorders in 1986. His foundation provided cochlear implants for low-income patients as well as funding towards research for hearing improvements. Through his foundation as well as determination to not let his blindness disable him, Charles broke down expectations and stereotypes for disabilities. In fact in 1994, Charles was honored with the Helen Keller Personal Achievement Award, which celebrates individuals who have improved the lives of disabled peoples.

First used in the 1960s, the cochlear implant is surgically implanted to provide sound to individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing.

National Museum of American History, 1997.0317.01.

Regan Shrumm is an intern in the Division of Culture and the Arts at the National Museum of American History. She recently finished her Masters in Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Victoria in Victoria, BC, Canada.