By Katie Knowles, museum cataloger

This story originally appeared on the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture website.

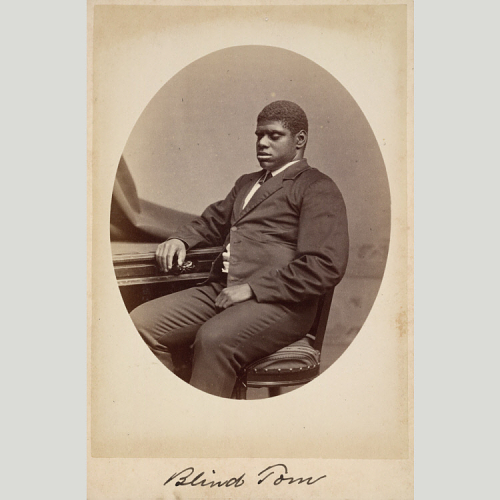

A flute found in the Museum's collection was made by one of the finest flute makers of the late nineteenth century, William R. Meinell. It is a beautiful example of a modern, high-end instrument of its time. While the flute has interesting material attributes, it is the story of the person who used this artifact, Thomas "Blind Tom" Wiggins (May 25, 1849 – June 14, 1908) a blind African American musical prodigy, that is truly fascinating,

During the late nineteenth century, Wiggins was one of the most famous pianists and popular performers in the United States. Born enslaved in Columbus, Georgia, his enslaver, James Bethune, discovered Wiggins' musical abilities and began holding public concerts when Wiggins was only 8 years old. His first compositions were published in 1860 when he was only 11. The Bethune’s continued to hold concerts featuring Wiggins throughout the Civil War with much of the proceeds going to support the Confederacy. Wiggins' best known composition, "Battle of Manassas," was composed in 1861 after he heard a recounting by a soldier of the first battle at Bull Run. Wiggins' compositions often sampled popular music and offer interpretations of natural and mechanical sounds.

From the Collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution

Biographer Deirdre O'Connell argues that Tom, blind at birth, was also autistic. Dozens of descriptions of those who saw his performances describe behaviors consistent with an autism. In addition to music, Wiggins' performances included mimicking famous speeches and spontaneous gymnastic feats. As an autistic, blind, African American in the nineteenth century, Wiggins was exploited at every turn. No one who controlled Wiggins career and the money made from his music and tours ever seemed to consider him as more than a lucrative curiosity. After the Civil War, Wiggins' parents signed a five year indenture to James Bethune. From 1870, when the indenture was up, until death from a stroke in 1908, Wiggins was under the legal guardianship of Bethune family members based on the argument Wiggins was "an idiot". While the Bethune family made thousands of dollars through their ownership and then legal guardianship of Wiggins, he would be buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in Brooklyn, New York.

Audience members often recognized Wiggins' joy in hearing their reactions to his music. It was apparent to many he enjoyed performing. Balancing what little is known of Wiggins' own perceptions of his life and career with the blatant manipulations of the Bethune family is a complicated task. Today, his status as a celebrated American composer and famous performer have been relegated to the margins of American music history.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

To see the additional objects related to Wiggins, visit the presentation on the website of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.