by Elizabeth McAlister

The phenomenon of Rara is both fun and profound. It is at once a season, a festival, a genre of music, a religious ritual, a form of dance, and sometimes a technique of political protest.

Album cover of Rhythms of Rapture: Sacred Musics of Haitian Vodou (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings).

Rara season starts along with Carnival, and keeps going through Lent, culminating on Easter Week. It is a paradoxical mix of both carnival and religion. Rara societies form musical parading bands that walk for miles through local territory, attracting fans with old and new songs. Bands stop at solemn spots—cemeteries, for example, where they salute the ancestors. Musicians play drums, sing, and sound bamboo horns and tin trumpets. These horns—vaksin—create the distinctive sound of the Rara. Each player plays one note, in a technique called hocketing, and together the band comes up with a melody. Then, a chorus of queens and fans sing and dance along to the music. The sound carries for miles around letting fans know that the Rara parade is coming.

This is an old festival, harkening back to slavery times in Haiti and, before that, in Western and Central Africa. Its songs and melodies have been passed down for generations, so they are all popular “hit” songs. The town of Leogane is best known for its Rara, but the festival is practiced all over Haiti and is different from region to region. Moreover, Rara is played enthusiastically in the summertime in cities in North America: Miami, New York, Boston, Montreal. “Rara makes me feel I am in my real skin,” said one Haitian in New York. For Haitians in the diaspora, playing or dancing in a Rara delivers the special ambiance of Haiti. It is a taste of home.

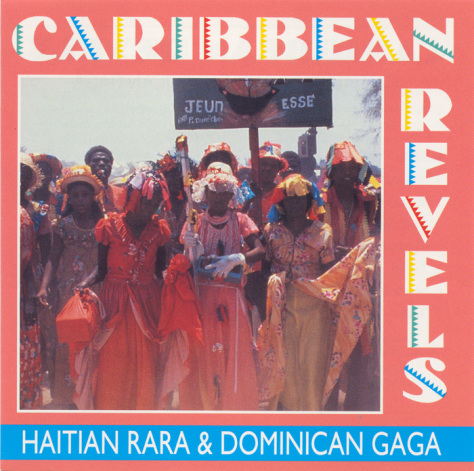

Album cover of Caribbean Revels: Haitian Rara and Dominican Gaga (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings).

Rara bands can be simple or complex. On one hand you have a cappella charyio-pye, or “foot bands.” These bands stomp the feet in a marching rhythm that creates the tempo of the song. At the other end of the spectrum are the Rara bands in the town of Leogane, which has established a national reputation with its use of brass musicians from konpa (popular dance) bands. These bands produce catchy melodies at a high volume that can be heard far away.

The typical Rara orchestra consists of three drums followed by three or more bamboo instruments called banbou or vaksin, metal horns called konet, several waves of percussion players with small, hand-held instruments, and finally a chorus of singers. There is also usually a core group of performers—eithermajò jon (baton majors) or wa and renn (kings and queens)—who dance for contributions.

The drums played in Rara are almost always goatskin drums used in the Petwo lwa (spirits) family of Haitian vodou religion. These drums are strung with cord and tuned by adjusting small pegs in the interlaced cords along the drum body. The Rara drums must be portable for Rara and must be light enough to carry for miles of walking and playing. So the manman, segon, and kata of Petwo ceremonial drums are replaced by a more portable ensemble of manman, kata, and bas. The first two are single-headed drums, strapped to the body by a cord across the shoulder. A kès (a double-headed goatskin drum played with two sticks) can be used as the kata. The bas is a hand-held round wooden frame with goatskin stretched across the top and interlacing tuning cords creating a web along the inside of the drum.

Vodoun "manman" drum in the collections of National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

The banbous, or vaksin, are the instruments most immediately associated with Rara music. They are hollowed-out bamboo tubes with a mouthpiece fashioned at one end. Each banbou is cut shorter or longer so as to produce a higher or lower tone: bas banbou is long and gives a bass sound, and charlemagne banbou is short and is pitched high. Other tones fall in the middle. Each player takes the instrument and blows a tone. Together, the group of vaksin players improvises until they find a pleasing, catchy short riff, each player blowing at a certain point to create a melody in a hocketing technique. To help their timing, the vaksin players beat a kata part on the bamboo with a long stick, making the instrument both melodic and percussive.

Rara as a Religious Obligation in Vodou

In my book, I argue that while Rara seems like a country Carnival, the festival consists of an outer, secular layer of Carnival “play,” that surrounds a protected, secret inner layer of religious “work.” Most Rara bands have a lwa (spirit), who serves as its patron in the Afro-Creole religion of Haiti (called Vodou). Often it is the spirit who has asked for the band to be formed, and the Rara is itself a gift to the spirit.

The inner core of Rara leaders is made up of leaders of Vodou societies. They are going about the business of performing serious ritual obligations to the lwa. Rara bands work to “heat up” and activate their instruments, and they perform ceremonies to the spirits. Then, the bands go out to salute important religious sites—graves of ancestors, trees, rocks, and intersections where other inherited spirits are said to live.

The Rara spirits can sometimes be from the Rada branch, which is historically Dahomean and Yoruba. But most often, they belong to the Petwo branch, which is rooted in the Kongo civilization. The rituals, rhythms, colors, and dances of Rara are close to the Petwo and Kongo rites. The festival is a spiritually “hot” festival, and by necessity takes place mostly outdoors, and not inside the Temple itself. Occasionally, Rara bands will even go to the cemetery to ask for permission to capture the spirits of the recently dead—called zombi—and bring them in the Rara to “heat up the band.” This is a very complicated ritual. For a longer and more sensitive discussion, read its historical analysis in chapter three of Rara! Vodou, Power, and Performance (University of California Press, 2002).

Rara as a Form of Carnival

Rara season overlaps with Carnival season, and so Rara activity begins on January 6, known in the Christian calendar as the Epiphany. Rara bands usually parade as small carnival bands, and then continue to parade after Carnival, during Lent, until Easter. The “tone,” or “ambiance,” of Rara parading is loud and carnivalesque. If you don’t know about the hidden, religious core of Rara, you’ll think that Rara is simply a matter of young people exhibiting their talent at singing and dancing in a boisterous, rebellious atmosphere. As in Carnival, Rara is about moving through the streets, and about men establishing (masculine) reputation through public performance. Rara bands stop to perform for noteworthy people and to collect money. In return, the kings and queens dance and sing, and the baton majors juggle batons, and even machetes! Rara costumes are known for their delicate sequin work, which flash and sparkle as the batons twirl. There is a lesser-known costume, too, of colorful streaming cloth hung over knickers and hanging from hats. The competitive music and dancing, the sequins, and the cloth strips are all echoes of festival arts in other parts of the Caribbean. In its orality, performative competition, and masculinity, Rara shares similar characteristics with other Black Atlantic performance traditions like carnival, Junkanoo, capoeira, calypso, blues, jazz, New Orleans’ second line and Mardi Gras Indian parades, reggae, dance hall, hip hop and numerous other forms. Unlike many Afro-Creole masculinist forms, however, Rara is explicitly religious.

Notes excerpted with permission from the author’s website and from her book, Rara! Vodou, Power, and Performance in Haiti and Its Diaspora (University of California Press, 2002).

Related

Rada Drums at the National Museum of Natural History: Boula Drum, Segon Drum, Manman Drum

“Some Kind of Something Is Going On Down There”: Crossroads at Congo Square," by Robert H. Cataliotti, Folkways Magazine

Vodun-Rada Rite for Erzulie, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Music of Haiti: Vol. 2, Drums of Haiti, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Life In a Haitian Valley Film Study, 1934, Human Studies Film Archives, Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History

Afro-Caribbean Dance Traditions: Cuba, Haiti, and Brazil, 1986-1992, Human Studies Film Archives, Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History