By Regan Shrumm

Before record albums, broadcast radio, and iPods, brass bands satisfied the national craze for music. These bands were the centerpiece for parades, military events, and circuses. Even companies created bands as a type of workplace community gathering. In fact, during the “Golden Age of Bands”—the period following the Civil War through World War I—there were over 10,000 amateur town bands alone. While music was often seen as a feminine activity, due to its military origins, the brass band was distinctly masculine. However, a few women throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries began to make all-female bands commonplace.

During the early nineteenth century, part of every wealthy girl’s education included learning to play the piano and sing. As cities and the merchant class grew, musical accomplishments also became a standard of the middle class. Still, the musical instrument repertoire for all women was small. Women were often discouraged from playing orchestral instruments as they either did not look lady-like or producing sound from them required too much strength. Some stringed instruments, like the violin, were associated with the devil; therefore, respectable girls generally did not play them.

A ca. 1902 photograph of the Helen May Butler and her Ladies Military Brass Band from the National Museum of American History Archives Center.

In 1891 in Providence, Rhode Island, Helen May Butler experimented with an all-female band named the Talma Ladies Orchestra. The band slowly grew from less than two-dozen members to a twenty-piece band, and though they performed only at private functions, by 1901, the band became well-known enough to have a sponsor and business manager. That sponsor, John Leslie Spahn, renamed the band Helen May Butler and her Ladies Military Brass Band. The band toured the country, and even attended several world’s fairs and expositions, offering “Music for the American people, by American composers, played by American girls.” Though the band dissolved in 1913, Butler was still popular enough to attempt a 1936 run for a U.S. Senate seat in Kentucky.

Butler’s band became nationally recognized, but even in the 1940s all-female bands were still very rare. A few local all-female bands cropped up in such places as Ashland, Oregon and Belleville, Wisconsin. Some music companies, like N. N. White of Cleveland, even developed special lightweight musical instruments that claimed they were “appropriate” for females to play.

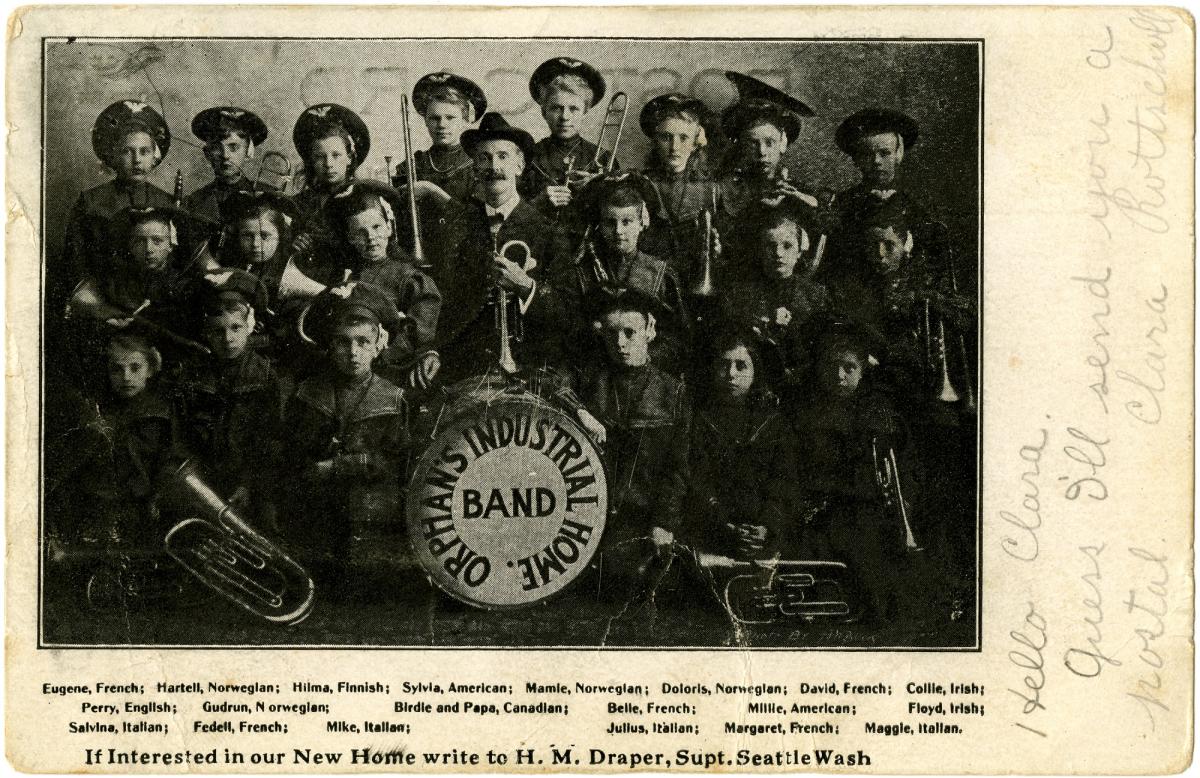

A mixture of girls and boys in the Orphan's Industrial Home Band from Seattle, Washington in 1906. Hazen Collection of Band Photographs and Ephemera, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

However, there was an even bigger struggle in integrating women into all-male bands. Lecturing at several music conventions, including the Women’s Musical Congress at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, French violinist Camilla Urso demanded that women be admitted to bands. She even wrote a letter to the editor of Musical Courier in 1898, stating: “Let my sisters agitate this question and assert their rights. It will in time benefit women with scanty means who have spent their time and money, when now men alone perfect.”[1] Even toward the beginning of the twentieth century, when men and women began to play together in recreational activities, there was still prejudice about women joining male bands. One Iowa bands woman remembered a conductor shouting at her “I wouldn’t have any damn girl in the band. You can’t talk like you want to!”[2]

Virgil Whyte's Musical Sweethearts, ca. 1943. Silver gelatin photographic print by unidentified photographer. Virgil Whyte "All Girl" Band Collection, NMAH Archives Center.

Swing music developed in the early 1930s, but it was not until World War II, when millions of men left for military service, that all-women swing bands really gained acceptance as entertainers on the home front. The Ingenues and Valaida Snow’s all-female swing band toured throughout the United States, while Ada Leonard’s All-American Girl Orchestra was the first all-women band to be officially signed by the USO, performing to army camps during World War II. However, as women’s bands historian Sherrie Tucker points out, scholars have neglected many of these bands. Because there is little documentation on these bands, their impact on music history has not yet been thoroughly acknowledged by researchers.

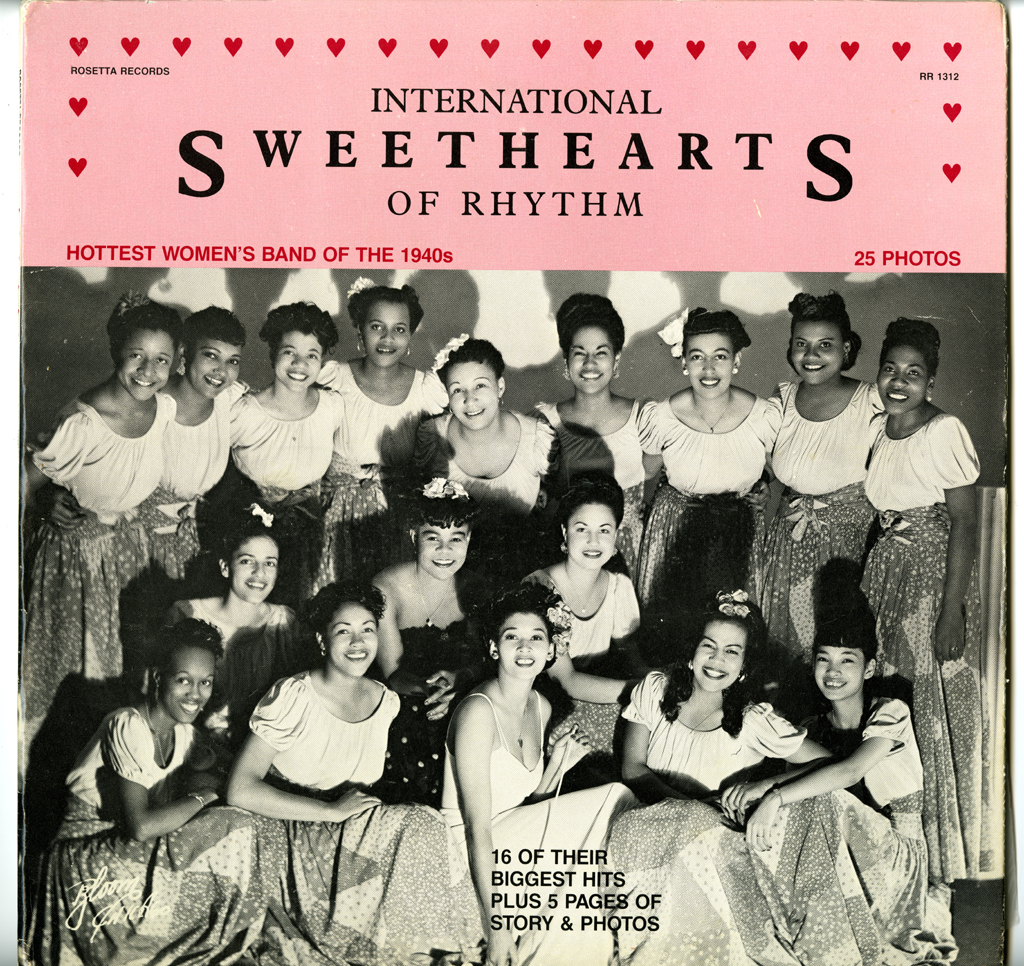

However, the first integrated all-women’s band, the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, was rediscovered by feminist scholars in the 1970s and quickly became a symbol of second-wave feminism. The band originated in 1937 from a fundraising initiative for the Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi. From the outset, the band included African American, Latino, Asian, Native American, and bi-racial women, and in 1943 began inducting white women. At that time it was dangerous for an integrated band to travel in the south, so the white and lighter-skinned African Americans had to darken their skin in order to blend in with the rest of the band, Despite this, there were still many incidents of harassment, and even arrests, that occurred throughout the band’s twelve-year existence.

A September 1944 performance of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm from the National Museum of American History Archives Center.

The situation for female musicians changed in 1974, when the U.S. Congress passed the Equal Opportunity in Education Act, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, sex, religion, and national origin in public elementary and secondary schools. This act provided the momentum for gender integration in college, military, and concert bands. Though all-women brass bands are now a thing of the past, these groups paved the way for equality today and set a precedent for all-female bands such as the jazz group Diva and the rock duo Indigo Girls.

Those interested in more images of all-female bands may visit the Helen May Butler Collection, the Hazen Collection of Band Photographs and Ephemera, and the International Sweethearts of Rhythm Collection from the National Museum of American History Archives Center.

Regan Shrumm is a Culture & the Arts intern at the National Museum of American History. She recently received her master’s degree in Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Victoria in Victoria, BC, Canada.

[1] Jane Bowers and Judith Tick, ed., Women Making Music: The Western art Tradition, 1150-1950 (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 327.

[2] Margaret Hindle Hazen and Robert M. Hazen, The Music Men: An Illustrated History of Brass Bands in America, 1800-1920 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987), 57.